“I want the primitive effect you get when you bring together abstraction and the real together”

(Andrew Wyeth)

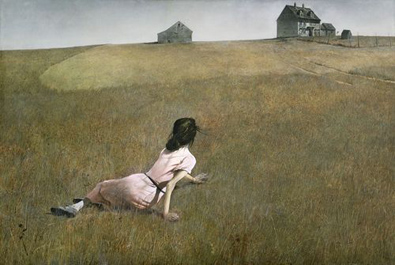

Christina's World seems to be laid out into the open, unfolding itself in a minimal interplay between figure, field and the houses on top of the hill that mark the horizon. The figure is leaning and projecting herself and her gaze expectantly towards the bigger building, as if she is in the middle of a movement intending forwards and upward.

The direction of the unseen gaze, the leaning towards the house up-hill, may be experienced also as inspiring hopeful expectancy, promising, perhaps, fulfillment of a longing for home.

However, this world that spreads open between figure, field and longed-for home, hides an inner tension, that festers as constant disturbance, the more we contemplate it. The more we do, the stronger become the tension and disturbance. The very openness of the scene begins to reveres itself. If we pay attention to this subtle, self-covering, reversal, it is experienced as circumvented on both sides: by the crawling figure on one hand, whose posture now suggests an arrested movement, a gesture that appears almost animalistic in its concentrated power of arrested striving, and by the gray, non-transparent horizon on the other, which may seem now as blocking the path forward and, at the same time, displacing and distancing the longed-for home.

The density and contractness of this limited world, contrasts starkly with its first appearance. It produces an almost physical effect that can halt our breath, even become psychologically oppressive, as we experience a tightly enclosing, narrowing, attraction between two movements, an arrested-expansion movement of the striving-crawling figure and the intensely contracted-opening movement of the promising hill-houses-horizon.

An obstruction of the will, of movement and of freedom, is experienced, through which a non-spoken, inwardly intensifying, anguish, is felt.

Wyeth’s world unfolds and actualizes this tension in all stillness, in perfect calm, orchestrating- with minimalist means- an invisible process of arrhythmic, protracted, even spasm-like, folding and unfolding and refolding, spreading and gathering again of blocked intensities, an extractive operation enhancing itself inwardly, imperceptibly, and continuously.

This appears to be the “primitive effect” Wyeth is striving for, when he brings together what he calls the abstract and the real. (See quotation, above). But his “primitive effect” is nothing primitive or given; its production is one of his secret creative technique; he is a master of producing these “primitive” effects, by means of his ability to discover, unearth and liberate an arrested movement, physically hindered will, preferably where it is not externally visible at all, where it is rather wholly absent: in stillness itself.

As a matter of fact, the production of “real-ness” through Wyeth’s style has nothing to do with “realism” or “magic realism” commonly attributed to him. ("Magical realism” could have indeed been used, but then only if "magical" would be connected to Novalis' wholly distinct meaning of the concept). Wyeth's real is the end result of a long process of productive realization (actualization), he isn’t interested at all to reproduce what we grasp as given with our senses and mind (realism), nor with imaginary effects that would conjure an improbable, haunting and strange world (magical realism). The haunting feeling that many experience with his paintings, its “strangeness” (Marc Rothko felt this to be Wyeth’s main characteristic), is precisely the haunting of the real itself, produced by the painter. Reality must be first produced, and art’s task is to transform the un-real world of ordinary human perception into reality. The world of true art isn’t reproduction of the given, or fantastic creation of imaginary, non existing worlds; but creation of the real world, which, without art, would remain hidden and forgotten in the given.

Wyeth’s power is an operation, a technique, whose purpose is to extract a consistent essence out of the given and the painting is made of this truly “magical” substance. We may glimpse an inkling concerning its production process if we pay closer attention to Wyeth’s words: “I search for the realness, the real feeling of a subject, all the texture around it...I always want to see the third dimension of something, not a frozen image in front of me...I want to come alive with the object...”.

Wyeth’s creative production advances therefore in this order of enhancement:

First, the subject's feeling is released from its existential, realistic, personal, imprisonment (say, Christina's anguish), then, second, its surrounding texture is gathered and condensed (the open as such must first be created, in order to be brought to bear, to embrace and carry the released anguish), third, its third dimension is laid out as a plane of composition (a plane which dimentionalizes the arrested freed anguish, spreads it out into the impersonal, non-organic, real open field, where the subject can metamorphose itself, flow and spread it's real wings into the open cosmos), and fourth, the artist has thereby truly become his object, or subject (he becomes Christina, takes on, releases, and transforms, her existential place, frees her will, so she can become her real self), and the mature work embodies both his becoming subject and the subject’s growing into the free space of its real free becoming.

These four stages of enhancement are not subjective experiences of the painter, but stages of real becoming, the becoming and making of the reality of Christina’s world, whose components are abstracted (extracted) from the subject, and made gradually more real, that is, consistently objective.

Wyeth is after the potential, real, unseen, will, not the extensive, expanded will power, but the intensive will power, that is actualized when it flashes up as “primitive effect”, when arrested expansion (the real as given) and opening contraction (abstraction) disjunctively interpenetrate and impregnate- without annihilating- each other.

This is Christina’s world, which is indeed Wyeth’s world: the work of producing an external revelation of the purity of the hidden, arrested, anguished will, freeing it to its becoming free will as infinite acceleration, actualized in and through the places in which it is most arrested. “I want to come alive with the object” means: to become the object, which is, in this painting, Christina’s world, and by becoming her world, free her anguish, her arrested will, and let it become an eagle’s flight, becoming an infinite free survey and homecoming, embracing figure, field, houses and open horizon.

(The same technique, applied not to the arrested bodily-physical will but to the arrested will of thinking, is also one of Becket's most creative poetic techniques; The affinities with another great contemporary American artist, Robert Wilson, in this regard, will have to be explored elsewhere).

Read more about Art & Event in my book, The Event in Science, History, Philosophy & Art

עברית

עברית